I recently had the pleasure of receiving a very special camera from the Ukrainian Film Photography Community. Vitalli, one of the members, got in touch after watching my YouTube video about the Zenit B, a popular Soviet-era camera. They kindly suggested that while the Zenit has its fans, there might be better options out there, and offered to send me a Kyiv 19 to try. How cool is that? And before they sent it they also had the camera serviced! So I know I am in for a treat!

Now, I’m not one to get hung up on the technical specs of a camera. As long as it captures an image, I’m happy! Give me a lens, some film, and a photographic challenge, and I’m all in. But I also appreciate that there are passionate camera connoisseurs in the film community who possess a wealth of knowledge about all sorts of cameras – the good, the bad, and the unusual. Their expertise is invaluable!

The community also sent me a lens with the camera. A Helios 81H 50mm F2. I’ve never owned a Helios lens before! More on the lens soon!

Kiev 19

Let’s get straight into it! This camera is built like a Russian steam train! As is the Zenit B too! So no fear if you drop it! Just don’t drop it on your foot!

The Kiev 19 was produced in the mid 1980’s by the Arsenal factory in Kyiv, Ukraine and continued into the early 1990’s. Back then Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union. The camera is commonly known as KIEV? Even though the Ukrainian capital is KYIV, when it was under Soviet Union the name was KIEV.

It is a very simple camera and I found it comfortable to shoot.

- Speeds – 1/2 – 1/4 – 1/8 – 1/15 – 1/30 – 1/60 – 1/125 – 1/250 – 1/500 (Bulb)

- ISO – 12 – 400

- Average Metering

- 2xLR44 Batteries

- Hot Shoe / Sync Port

- Vertically-traveling metal focal-plane shutter

- Stop Down Metering / DOF Preview

- Strap Lugs

- Micro prism viewfinder with 93% coverage

- Lens mount – Nikon F

I found it strange that the shutter speed started at half a second and missed out the normal 1 Second time. But let’s face it. Most of us will be at 1/60th and above.

The ISO range on the other hand, the meter only accounted for films up to 400 speed. So if you want to shoot a 3200 speed film and rely on the meter you will have to compensate yourself using the shutter or lens aperture. I did wonder why Arsenal limited it to 400.

Focusing with the camera was very easy as it has a micro prism viewfinder inside so there is no problem getting a nice sharp focus on your subjects. Composition wise the viewfinder, apparently, covers 93%.

For me the real bonus of this camera in the lens mount. It is Nikon F! Which means I can use some of the Nikon and other Nikon F fit lenses that I have. But what about the Helios Lens?

Helios 81H

The Helios 81H 50mm f2 is a hidden gem from the Soviet era, and a fantastic lens to pair with the Kiev 19. It’s a fantastic lens that offers a unique combination of sharpness, character, and affordability. I’d say It’s a great choice for photographers who want to experiment with a classic Soviet lens. It feels tough, well made, has coated glass and smooth aperture blades and focusing. But I did notice one slight issue.

I put the lens on my Nikon ZF camera and here are some of the images.

I did notice with small apertures on darker subjects there is a slight haze in the centre of the glass that is visible and I really am not sure why this is. Even after inspecting the glass I could see no obvious signs.

Kiev 19 & Helios Lens.

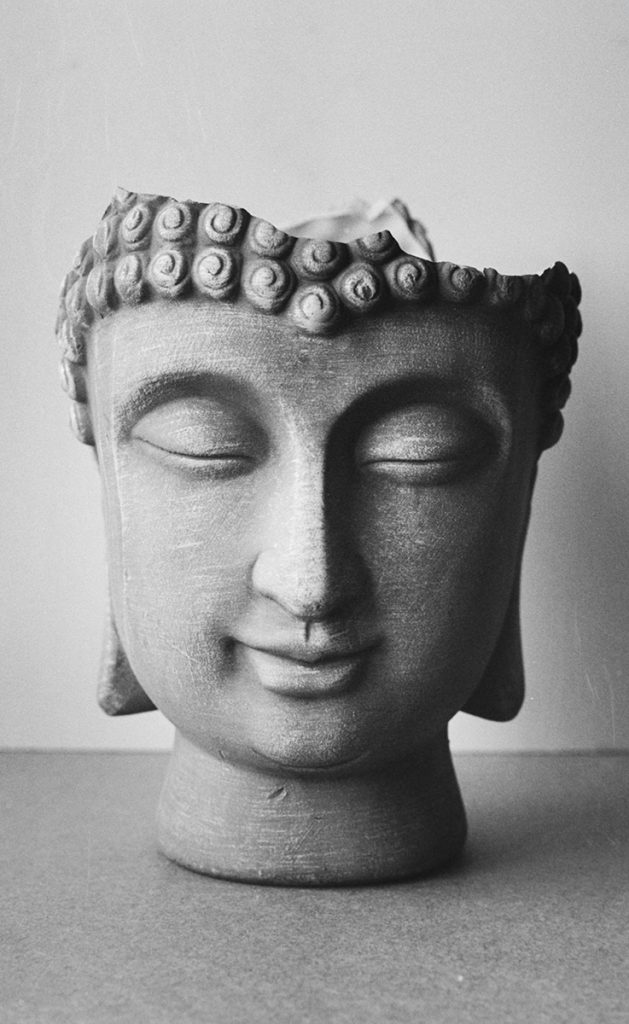

For my YouTube Vlog I went to a few various locations loaded with an expired roll of Kodak 400CN Black & White Film. I have a few rolls of this film and it works fine, even though it is a C41 process film I developed it in Black & White Chemicals. I like the look. Contrasty and a bit of grain.

Metering

As I mentioned the camera has an internal metering system and with this camera being recently serviced it was very accurate. Inside the viewfinder it just shows a PLUS and a MINUS on the left hand side and when both are lit that means your exposure is correct. For the meter to work you need to use the Stop Down Lever (DOF Preview).

This photograph I took using the cameras internal meter, which I double checked with my Sekonic incident meter. F5.6

Conclusion

As I said earlier I’m not a camera geek. As long as a camera works and can take pictures with it then that’s all that matters. Even if a camera I have isn’t comfortable to use on a daily basis it’s still nice to own it and shoot it now and again, such as the Praktica MTL5B. I find the exposure button on that camera uncomfortable but it’s still nice to load and shoot.

This KIEV 19 I found to be comfortable and I’d have no problem using it all day for some street photography. And taking Nikon glass is an added bonus!

For total beginners I’d say it’s possibly not the best camera as the metering only accounts for films up to 400 ISO, but if you’re comfortable with shooting in manual and know your photography then it’s ideal you are looking for something a little different. As for the price I can see these online for less than £100 with a lens! So I wouldn’t say it’s in that bargain range as there are many other great cameras for similar price. Unless you are looking for a Soviet camera. If you are a Nikon shooter you will find the F mount exciting as I did.

Reliability

Looking online there is a mixed bag. While the Kiev 19 might not be as reliable as a modern camera or a top-of-the-line professional model, it can be a solid and dependable shooter if you take good care of it. Many photographers still enjoy using the Kiev 19 today, and with a bit of attention, it can provide years of photographic enjoyment.

Finally

Finally Vitalli sent me an interesting read about Soviet cameras and the manufacturers. I will leave you with what he said.

The Western film community often dismisses Soviet cameras as nothing more than exotic, unreliable display pieces. This perception holds some truth but does not tell the whole story. Cameras produced in the USSR often seem archaic and peculiar, and this impression is frequently accurate. However, to understand why, one must consider the context and circumstances under which they were created. In this account, I aim to explain why the Kiev-19 camera is special and worthy of attention.

The Soviet Camera Industry: Three Key Players

There were three major photographic equipment manufacturers in the USSR. The first was KMZ, the most well-known internationally. Their cameras showed minimal progress from model to model, and their top product at the time, the Zenit-19, exhibited worse reliability than the cheaper Kiev-19 during tests conducted internally by KMZ. It is worth noting that the Kiev-19 bodies used in these tests were obtained through the State Optics Institute (GOI) and had already undergone rigorous state trials, meaning their mechanisms were significantly worn. Despite this, Zenit cameras were produced in massive quantities and widely exported.

The second major player was LOMO, the company that inadvertently gave rise to the lomography movement by producing compact cameras so flawed they became appealing. When tasked with creating a professional camera to compete domestically with Nikon’s F-series, LOMO developed the Almaz lineup. The Almaz-103, for example, was so unreliable that repair shops were overwhelmed with returns, and production ceased due to the design’s complexity and lack of durability.

Finally, there was Arsenal, which, in my opinion, was the only Soviet manufacturer truly dedicated to its craft. While KMZ might have been indifferent due to its primary focus on military production, the same could be said about nearly any Soviet factory. KMZ’s list of military products was similar to Arsenal’s, yet Arsenal consistently produced cameras of higher quality. Arsenal’s photographic division was a logistical challenge for the plant, which primarily manufactured gyrocompasses for missiles such as the SS-21 and SS-18, as there was insufficient space for both operations.

The Kiev Camera Lineup

One could write extensively about favoritism and other factors that limited Arsenal’s exports compared to KMZ, but for brevity, here is a summary of the Kiev-19’s history. The lineup began with the Kiev-17 and included three and a half released models (the 17, 20, 19, and 19M) and two unreleased models (the 18 and 21).

The Kiev-20 was never intended as a professional camera—that role was reserved for the Kiev-18—but it accidentally became the best Soviet SLR. Priced at $352 in 1985 (including a Helios-81 lens), it was too expensive for the general public, leading to the development of the Kiev-19. The Kiev-19 was designed as an entry-level SLR, priced at around $110. To reduce costs, features like the AI ring and a sophisticated mirror-lifting mechanism were removed, replaced with simpler designs. Despite these changes, the camera remained extremely reliable, even under harsh conditions. Criticism of its metering system often stems from confusion with the Kiev-20, which used in-house microchips prone to failure from slight overvoltage. The Kiev-19, however, resolved this issue.

Why the Kiev-19 Stands Out

The Kiev-19, produced from 1985 to 1991, was a simplified version of the Kiev-20 from the 1970s. It omitted features like a self-timer, multi-exposure capability, and a broader shutter speed range (limited to 1/2–1/500 seconds) to make it more affordable. It used a Nikon F-mount, allowing compatibility with Nikon lenses, though some lenses could jam in the mount. The Kiev-19 was praised for its reliability and ease of use, producing high-quality images even with its standard lens. However, it remained virtually unknown in the West, as it was not exported like Zenit cameras. The unauthorized use of the Nikon F-mount also prevented official sales outside socialist countries.

The Soviet Photography Landscape

The Soviet Union was a vast country where photography became a popular hobby due to limited entertainment options. However, the industry prioritized military equipment, leaving consumer goods as an afterthought. Mass-produced plastic cameras like the Smena and Lubitel were widely available but often of poor quality. Serious hobbyists faced limited choices, and what was available was frequently defective straight from the store. Professional photographers, especially correspondents for major newspapers, relied on imported modern cameras, which were prohibitively expensive.

In the 1970s, several Soviet factories began developing professional SLR cameras. KMZ produced the Zenit-19, LOMO the Almaz-103, and Arsenal the Kiev-20. While the Zenit and Almaz models were plagued by reliability issues—certified service centers even refused to provide warranty repairs for Almaz cameras—Arsenal’s Kiev lineup was reliable and user-friendly. This was largely due to Arsenal’s advanced production culture, which stemmed from its work on high-tech products like missile guidance systems and spacecraft components. Arsenal also had prior experience with high-end professional equipment, producing the Salyut (a copy of the Hasselblad 1600F) since 1957 and developing innovative automatic SLR cameras like the Kiev-10 and Kiev-15 in the 1960s and 1970s.

The German Influence

Arsenal’s photographic division benefited from the post-World War II relocation of the Contax factory from Germany to Kyiv. This included equipment, documentation, and even German engineers who helped establish production. The legacy of Contax craftsmanship influenced the high quality of Arsenal’s cameras, which consistently outperformed other Soviet-made models.